How We Learned to Love Disembodied Space and Reflections On the Nature of Books

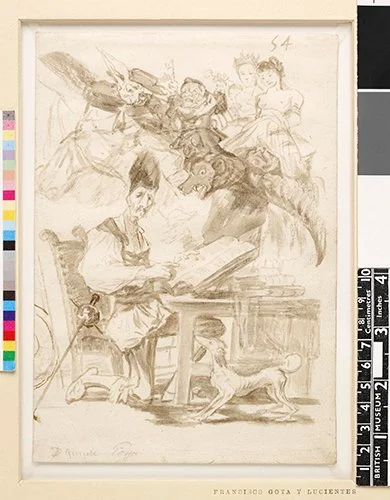

Don Quixote beset by monsters; Quixote sitting at a table, with an open book upon it, a dog near his feet and above his head monsters. c.1812-20

Brush drawing in grey-brown ink and wash by Francisco de Goya, British Museum of Art.

In a recent book review by Kevin Stroud of Dan Jones new book, “Powers and Thrones, A New History of the Middle Ages”, Stroud references a comparison Jones makes in his book between how early monasteries conveyed information across physical space to how Amazon and Facebook transmit data today. The book has been getting a lot of attention. One reason for that attention might be that life under COVID is dark. It is even darker under the shadow of totalitarian patterns emerging in the USA. Kleptocratic fascists seem to be bearing down on America in a relentless tide of psychological terrorism. Life in America now seems like a pretty dark and chaotic place to live in. Jones’ point with his entire book is that the Middle Ages weren’t dark at all and in fact was a time when progressive order emerged from chaos. The implication is that we too might emerge from these chaotic shadows into some semblance of redemptive and salubrious order.

The thing is, from the POV of physics, chaos is a necessary step towards a new order. In fact, it may be the inevitable sign that a new order must emerge. Theoretically, the outcome of chaos is impossible to predict. Stroud and some others believe the arc of history tends progressively towards greater and wider happiness. But is that true? There is no guarantee that the order that would arise from chaos would be beneficent. My trigger point theory speculates otherwise but it hasn’t been adequately tested yet.

As we stumble through what often seems like this endless dark age of COVID, in a state of menacing chaos, I can’t help noticing how quickly if not happily, we have adapted to an increasingly disembodied world. Arguably and frankly, right now a disembodied world seems much more inviting than the one we seem stuck in right now, helplessly imprisoned in a vise between climate change and fascism. Even as I write of those fears, I am aware that COVID has not only pushed many of us deeply into a more consuming virtual world. But at the same time, that virtual world is increasingly dissolving previously immutable boundaries we may need to dissolve right now in order to come together as a species under siege from each other.

Today I completed assembling a Zoom for ecoartspace. Feb 17 that had to take into account time zones from Australia to the Middle East. Once on line, we will no doubt sink into an easy meta-familiarity that both belies and connects our respective biogeographies. The Zoom will be titled, “Changing the Paradigm: Ecoart in Action” at 1: PM MT.

It will be one of a series of events to explore the ideas in “Ecoart in Action.” This one is with the co-editors and our publisher, Lynne Elizabeth, the founding director of New Village Press (NVP). The Zoom will allow us to overcome boundaries in an international conversation we need to have: how might art overcome global boundaries to rescue us all?

What has interested me most about publishing with NVP has been to consider the niche it appears to be inhabiting and expanding in, one that has its roots in the same monastic intellectual self-discipline of the medieval monasteries that evolved into our contemporary universities, the same institutions which seem under siege now from current realities, fleeing the disembodied threat of a virus, biological or political, into a disembodied virtual world, and arguably devolving into Facebook, as per Jones’s insights. Could NVP be part of an emergent knowledge model- a publishing company that isn’t an academic press sited in a physical university but that has scholarly standards which manifest as physical books?

The thing about darkness and chaos is that it is necessary for evolution. The trick is to maintain some semblance of order along the way to minimize casualties and collateral damage. Right now, we don’t seem to be doing very well in that area. January 6, 2021 was an example of our failure. On the other hand, some thinkers believe January 6, 2021 was a gift because it has drawn attention to the ubiquity of violent American insurrectionists.

Still, while we fail and educate ourselves, globally, there is increasing collateral damage. The recent controversial satirical film, “Don’t Look Up,” has hit a nerve about denial in the face of globalized lethal chaos. The hit TV series ’Succession.” has hit another kind of nerve. The latter portrays a number of odious characters indulging their gross entitlement as they jockey for power without any regard for the underclass of the 99.9% they exploit and in effect, murder. Both these film events are about chaos in time. In “Don’t Look Up,” time literally rushes forward as people dither. In “Succession,” the impending event that frames all other events is the aging of a tycoon who must pass his empire on to others. The others don’t dither at all about vying for that prize but they dither over other things, like love and accountability.

Alternatively with watching moving images on a screen, I am taking a hefty paper version of “Don Quixote” under the covers into bed with me. “Don Quixote,” in the original Spanish was my mother’s favorite book. Cervantes is now getting serious attention from me for the first time in decades, perhaps, ever. Lauded as the first modern novel, “Don Quixote” portrays a pathetic anti-hero, driven mad by his academic obsessions about chivalry, wandering the Earth oblivious to reality in a chaos of his own making. “Don Quixote” is just as fresh now as it was over 400 hundred years ago. Early in the book two seminal events are described. One is the wanton burning of his priceless collection of books on chivalry at the hands of Don Quixote’s community: his housekeeper, his niece, and his priest, under the assumption that these books have brought on Don Quixote’s madness. The other event is far more famous, the account of Don Quixote’s tilting at windmills which ends in self-inflicted personal damage. It is such a vivid metaphor that the very phrase, “tilting at windmills,” has entered common parlance to refer to engaging in a hopeless task out of misguided ambitions. In Don Quixote’s case, he imagined the windmills were dangerous giants he had to vanquish to defend his honor and protect his world.

I always carry a paper book on the subway. Lately, the book that accompanies me has been an abridged translation by Melanie Magidow of the lengthy epic story of warrior Princess Fatima from the seventh to the tenth century, in the region of the Arabian peninsula to what is now the border between Syria and Turkey.

The unabridged version is seven volumes and 6000 pages of rape, pillage, murder, kidnapping and politics in a culture with values not that different than medieval Europe at the time. The version I have is only 8” x 5” and 167 pages. Princess Fatima is a glamourous, swashbuckling conqueror who smites thousands to unite her people. She is the epitome of the chivalric character Don Quixote aspires to be except she is a woman.

About a century before Cervantes, Hieronymous Bosch did a good job of representing the hell of social chaos in a painting of the same name, “Hell.” Almost a century ago, Hitler did a very good job of harnessing hellish chaos to advance his insane world view. Humans seem very familiar with chaos. The question is, are we advancing towards a better order?

The menacing chaos of the world Cervantes represents endangers his protagonist much more than anyone else. More than two hundred years after Cervantes wrote “Don Quixote”, Francisco de Goya made drawings of Don Quixote’s chaotic mind. The menace is in an idea, in this case the archaic ideals of chivalry, disconnected from any real world.

In “Don’t Look Up,” the menace to the whole world is real but it is also an idea about danger and chaos people reject to their own destruction. In “Succession,” the menace is ubiquitous. The only “idea,” is greed for power over other people. In most cultures, that “value” is what makes the characters in the series so odious. Most civilized cultures recognize that untrammeled self-centeredness destroys society, except, apparently in the dominant culture of the world we now inhabit which promotes greed and power at all costs as a positive, commendable goal; to be a “killer”, is good. In the end, however, at least in the final episode, the value that overrides all the previous strife is the need for kindness, proof of caring.

A quote that has stuck with me from a NFT collector is to the effect that the exact idea of spending outrageous sums of money for a disembodied and meaningless virtual “object” is exactly the point: the extravagant expression of irresponsibility is the goal. It is “cool.” In my recent experiments in NFT land, I am flirting with disembodied space connected to actual meaning: to ideas, walking wide-eyed into an arguably chaotic new world, looking to express a measure of caring.

Back at the home world of COVID land, as the schools that evolved from medieval monasteries devolve into a new chaos and become artifacts of a past order, besides virtual viewing, we still seem to have books. The appetite for books seems to persist as a pleasurable tactile experience of holding a physical object in our hands that draws us into a story that holds our interest. I was pleased to learn that my book, “Divining Chaos,” coming out with NVP, will be 9”x 6”, a size which comfortably fits into the readers hands. That size could be carried on the subway or to the beach. 9”x 6” is also the size of my iPad. Our cell phones are even smaller but arguably too small to really enjoy a lot of art. Both “Ecoart in Action” and “Divining Chaos” will be available as e-books.

As the conventional academic world struggles to find new footing disembodied from physical real estate, and we explore the new frontiers of the virtual world, I am still looking for trigger points of emergence. Will paper books persist into the future as a locus of emergence even more than virtuality? Will that emergence lead us to hate or love? On an iPad we can access a film or an NFT in the same measure of space that can contain a history of a world or an account of a life. In the future, will all sources of ideas merge into one form in the same physical spatial dimensions, all portals leading into disembodiment? Will we invent a new word for communications that can contain almost all forms of art in a 9” x 6” object we can hold in our hands?

With both books I’ve been involved with, “Ecoart in Action,” and “Divining Chaos,” most of what I’m working on now is to generate interest in the ideas in the books by staging various events across the next several months. Technically, that task is marketing, Conventionally, sales/ marketing/ PR is associated with a process of competition and commodification that reifies the “win.” In our culture, the reasons someone can proudly say they are pleased to spend large sums of money on meaningless NFTs is that we live in a society that values individualism, competition and commodification. Sales and marketing is a tool to disseminate messages that vie for “eyeball” attention. The events that interest me most now for “Ecoart in Action,” are outreach to wider communities from a particular community with different values and goals than conventional $$ or power. The outreach work I will focus on later this year for “Divining Chaos,” will be an in depth look at how an individual can reimagine a relationship to community. In either example, the focus is on ideas in communities more than individuals.

Although books, iPads and other devices can equally place ideas in the palms of our hands, paper books feel different than machines made of plastic and metal. Whether on paper or viewed on plastic screens, ideas in books can effect hellish chaos as much as they can save lives. They can be weapons or balm. Books as paper objects or on a virtual device in themselves are neutral. Books are written to deliberately incite evil, to initiate a civil war or worse. The ideas in books like “Mein Kampf” or the “Turner Diaries,” continue to inspire collateral damage decades after their publication. Ideas in books can be manipulated for good or evil. Even passages from the bible can be taken out of context or interpreted to inspire violence as easily as love. Anne Franks’ Diary, was enlisted by North Korea to provoke hatred of the West. But books can also methodically guide enemies to find common ground, alert us to danger, inspire goodness and insight. Which ideas in what form will we hold in the palm of our future hands?

What all these artworks and artists have addressed is the space where we might find the answers to injustice, located in the space of our minds, held in our hands, arguably even more than physical locations. Will that change if we complete our adaptation to COVID? Can we adapt to all the other calamities our reckless relationships to the environment and each other have guaranteed? Going forward in these perilous times, how will we translate the ideas we hold in our hands, in our books? How might those ideas determine our future paradigms? If the translations we make unfold across a globe that lives simultaneously in virtual and physical space at various scales, will it express a beating heart of caring or doom us to dark, deadly terror?